In Chemical Resistance Part One: HOW? we established that misuse of a chemical intended to fight off a disease can lead to chemically resistant “critters”, or superbugs. I use the word critter to describe any pest that can cause a need for pesticide: be it bacteria, virus, fungus, insect, or weed.

But WHY would a chemical be used in the wrong way?

There are several reasons:

- Only one kind of chemical was used over and over again in the same place to kill the same thing.

- The chemical was used to kill the wrong critter.

- The wrong dose was used, so the chemical wasn’t effective.

In the first case, if we use only one chemical, and use it more often, more generations of the critter are exposed to it, selecting the superbugs faster. Think of it this way (yes, my husband is a Rocky fan). When a boxer is fighting, he needs to learn several moves and series of actions in order to take their opponent down. He wouldn’t think of fighting using only a right handed uppercut, would he? His opponent would be ready for him, and demolish him right away. They would know what to expect. Same thing with using the same chemical each time: the critter is prepared, and able to deflect the hit every time! It’s a superbug!

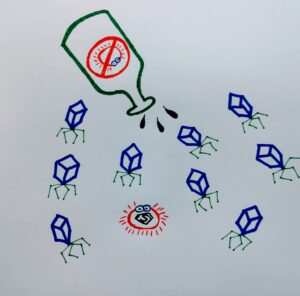

Remember how I described the “diversity” of critters that can harm plants (or us)? If you have a virus, and take antibiotics, the antibiotics won’t kill the virus, because that’s not what the drug was designed for. It’s made to kill bacteria. And any random bacteria that happen to be hanging out during your viral infection can hide out and is exposed to this antibiotic—having the opportunity to save the “memory” of the chemical. So the next time these critters overpopulate and you have a bacterial infection, that drug won’t treat it as well. The bacteria’s progeny will have a “memory” of the chemical, and more will survive. Enter: superbugs.

In agronomy, plant diseases are usually fungi. But there are also viruses and bacteria that cause plant diseases as well. If we aren’t positive of the source of a disease, and use a fungicide to try and kill a bacteria or virus disease, the fungi present—but not causing enough damage to trouble the plant—can develop a resistance to that fungicide.

In the third case, we see the importance of dosage. If you read your small print that comes with your antibiotics, it will urge you to take your medicine as directed, the full dose, and not to stop even though you feel better. Why is this? Your doctor wrote you a dose that will effectively kill the infection that is causing your illness. An effective “chemical storm” that will take care of those critters. If you stop early, or don’t take the whole dose correctly, you are diluting the chemical that the bacteria are exposed to. So more bacteria will survive: they don’t have to “hold their breath” as long or as forcefully, so to say, until the chemical storm is over. You might feel better temporarily, but when more critters survive, more critters have the drug “memory”, and those critters can create even more critters.

In a field, the agronomist takes into account many factors, such as the developmental stage of the plants, the type and severity of the pest infestation, time of the growing season, weather, and soil conditions. These factors determine the right kind and dose of pesticide to use. In a similar manner, if not enough of a pesticide is used, or if it isn’t applied at the correct time, more of the pest can survive and fight back.

Tune in for the third and final conversation regarding chemical resistance: WHAT TO DO? for information how we can treat and prevent superbugs from taking over the world…..

Thanks for reading!